Logocentrism and the Divided Brain

“If psychiatry were still interested in neuroses that make an organism or a society unable to survive in a state of Nature, then the logocentrism of our age [...] would have to be classified as a contagious mass hysteria” - Caribbean Rhythms, episode 93

In 2009, a book called “The Master and his Emissary” was published by the psychiatrist “Iain Mcgilchrist”. Mcgilchrist lays out an idea wherein he describes two different ways, or manners, of experiencing the world; each respective to the left and right hemisphere. Much has been long debunked regarding attempts to attribute certain things to one hemisphere, for example, that the left hemisphere is responsible for language while the other for processing images, or the idea that the right hemisphere is creative and feminine while the left is logical, rational and masculine. This is not the case, as is nowadays consensus. Mcgilchrist however takes on an entirely different approach. The interest for him lies not in what they do differently but in the how. And, in taking this approach, a picture emerges in which these two brain halves are shown to have two very different, and even mutually conflicting, mental experiences and ways of seeing the world.

In the 50s and 60s first experiments were made where they severed the corpus callosum, the nerve tract connecting the hemispheres. This was done to treat epilepsy patients and is nowadays a rare practice. But the experiments they did with these so-called “split brains” were very interesting. For example, when such a patient was shown an image in his left visual field (which corresponds to his RH) and was then asked what he had seen. Because the speech control center is located in the LH for most people and interhemispheric communication wasn’t possible, the patient was not able to name what they had just seen. He was however able to indicate a corresponding object using his left hand, since that is controlled by the RH. However, perhaps even more intriguing are reports of patients when having to choose between several options, like which clothes to wear, or to pick their favorite color. Here, oftentimes, the two Hemispheres would be in disagreement. This of course raises many questions about identity and the self. After all, it would suggest that the “you” is really not one single unit but rather consists of two, different and often disagreeing parts. Nonetheless, Mcgilchrist makes the case that they should not be seen as two equal counterparts, each on equal footing.

The hemispheres themselves are not symmetrical. But what does this mean for the function of the brain if the two halves are asymmetrical? And why is the brain divided even in the first place? And it is not just humans who have these but many animals as well. The idea is that at some point in our evolution there developed the need for two different kinds of attention: one, specialized and focussed, dealing with what one already knows, and the other, vigilant and broad-eyed, with an open look, ready to register anything new and unexpected.

Mcgilchrist argues that the two hemispheres each relate to differing views of the world, different ways of dealing with experience and the world around them. He concludes that the popular notion of the LH being the more dominant, important and somehow also “scientific” one, does not hold up. It is very good in focused and specialized areas, with a detached and mechanistic understanding, but outside of that it is far inferior to the embodied and contextualized experience of the RH. And so where they fundamentally differ is in the nature of their attention. While one (the LH) narrowly deals with what one already knows, the other has a so-to-speak broad view of things, vigilant and on the lookout for new and unknown things. The RH is also the one that can understand metaphors and recognize faces, which neither the LH can on its own. In short one might say that the LH is better at language and understanding semantics, while the RH is superior in what Mcgilchrist calls synthetic gestalt faculties; shape rotation, if you will. The difference between left hemispheric knowledge and right hemispheric knowledge is very much akin to the difference between knowing something by acquaintance and knowing something purely by reason; like being friends with a person and knowing them well and knowing most of the important facts about a person yet never having met them.

It is important that one doesn’t mistake this as a dichotomy like imagination vs reason or art vs science; that is false. In fact both are needed for each of those but the reason for the primacy of the RH lies in its embodiment and primary experience. Thus, in contrast to the present world of the RH, there is the re-presented world of the LH. But this shouldn’t be confused as a subjective vs objective dichotomy. The LH worldview, according to Mcgilchrist, involves a representational and abstracted view of reality. One can think of it in contrast to the RH like a map in contrast to the actual territory. His thesis is, that although the LH has been crucial in the success of western civilization, it is now leading to its demise, as its worldview has taken complete dominance and the right-hemispheric, more subtle and embodied way of being has been forgotten. One such example of the limitation of the LH is its tendency to make up what is going on in a way that sounds logical and reasonable but is actually, when viewed with full context, very false. And this is coupled with an intriguing reluctance to admit that it is wrong when confronted on such matters.

Some may know of Julian Jaynes and his book The origin of consciousness in the breakdown of the bicameral mind, a very fascinating theory which posits that in the days of old, when it is said that the heroes heard the voices of the gods, that this was not meant as a metaphor but that they literally heard voices. These auditory hallucinations were communications from the RH, however due to the newly arisen introspective ability, they were perceived as external, as if coming from an alien mind. The reason we moderns no longer hear the gods is due to a breakdown of the bicameral mind; the two hemispheres, previously separated, are now merged. Furthermore, he posits that the disease of schizophrenia is a regression to this older, primitive state of mind, where the two bicameral chambers are separated. The problem with, which Mcgilchrist points out, is however the evidence points towards the opposite of all of this. For one, schizophrenia is very modern phenomena and is not constituted by a regression to primitivism and lack of self-awareness, it is rather the opposite: obsessive self-awareness, a sort of hyper-rationalism and a loss of connection to emotion and embodiment. Additionally, he puts forward the idea that what really happened was not the merging of the chambers but the separation of them; that before there was a unity of the mind and that due to the new separateness the question of “whose thoughts these are” arose.

The Renaissance and the romantic period were two movements which clearly relate to an emergence, though really a re-emergence, of right hemispheric ways of being and thinking. This is most obvious in the art of the Renaissance and the discovery of perspective and depth; also in the re–discovery of the body and a love for the body; prior lost for some time, then resurrected through study of the ancient greeks. But this is not exclusive to art. In the whole there seemed to have been a standing back, a gaining of new perspectives and a larger picture of things; yet not with the kind of left hemispheric detachment, namely that of secluding oneself from physical sensations and an embodied life, secluding oneself in a sort of hyper-self-awareness, like lost in a hall of mirrors. Essentially, there was a desire to leave behind the principles that one had been following and to try to perceive things as they are, without overly abstraction and prejudices of dogma and rationalization, as can be seen in the accomplishments of Kepler and Newton. This desire, very much itself reminiscent of the aforementioned right-hemispheric gestalt capabilities, is perhaps most clearly seen in the scientific works of Goethe, namely in his morphological method devised in his Metamorphosis of Plants. It was in the genius of the Greeks, where this faculty of clear perception was perhaps the most pronounced. It is also the Greeks who are praised by Nietzsche as the healthiest people to perhaps ever exist. They had a fullness and wholeness of life, which to the average modern contemporary would seem inexplicably alien. Yet in comparison, modern life seems mechanistic and inert; it is reduced and broken.

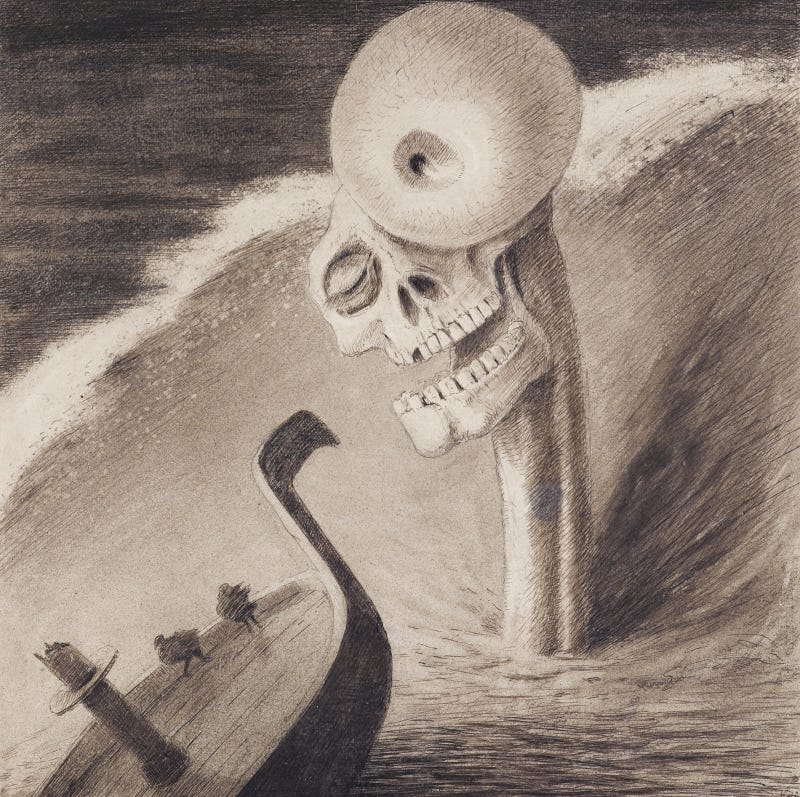

Goethe himself, who actually thought his scientific work was more important than his poetry, is the clearest example showing that the idea of “LH = science” and “RH = art” is a very shallow, and false, conception (indeed typical of left hemispheric reductionism). Goethe’s holistic science is an example of the sort of hierarchy between the hemispheres according to Mcgilchrist. Namely that of the LH as the servant and emissary to the RH; as a speciality, useful for manipulation and abstraction, but always in service to the synthesizing Master of the RH. Problems arise however when the servant starts to get under the belief that he is the actual master and starts to apply his technique or method of interacting and making sense of the world to areas which would normally be outside his speciality, outside of the areas where they work and for which they are intended. Then you get the type of narrow and reductionist thinking, which you see so rampant today: The confusion of words with reality, the confusion of the concept with the actual phenomena. To anyone who has been paying any attention in the last few years this will be nothing new at all: an ever-growing blindness to subtle truths, in favor of increasingly empty words and abstractions. The western world today is now in almost all regards a mere husk of what it was; of the lively and creative powers which it once had, there is no trace, and in their place a disembodied and excessively hyper-reflexive attitude, reducing life from what it could be.